Sitting atop a hill in Charlottesville, Virginia, rests Thomas Jefferson’s estate, Monticello. Jefferson built, and rebuilt, Monticello over the course of forty years; at one point significantly remodeling it to incorporate architectural elements he learned while serving in Paris as the Minister of the United States to France.

Inside, Monticello follows an annoying trend we’ve noticed increasingly at tourist destinations of prohibiting indoor photography, even after extracting an astounding $22 per-person admission fee. The photography prohibition has become so pervasive it is probably time to update the old traveler’s saying: “Leave nothing but footprints, take nothing but what you buy in the gift shop.”

A couple of photos would certainly help in describing the unique interior of Monticello. But suffice it to say, Jefferson used space in a way that isn’t all that common today. Rarely will you find a plain rectangular room. Instead, octagonal shapes predominate, often increasing light flow from multiple directions. Most interestingly, Jefferson’s office extends seamlessly into his library forming a barbell shape that extends the length of the house. Throughout the estate, Jefferson incorporates design features innovative for the time, from revolving serving doors to triple hung windows that double as private entryways for guest quarters.

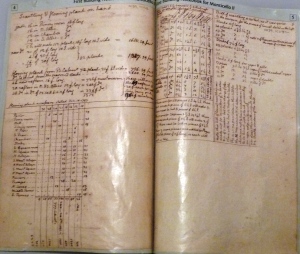

Probably the most striking thing about Monticello is the sense of Jefferson’s genius that one gets from the place. Jefferson wasn’t simply a gifted writer who penned great documents; or merely the 3rd U.S. President; or a political elite who commissioned some great buildings; he was all of those things, and more. Jefferson was a philosopher, an inventor, a voracious reader in at least four languages and a self-taught architect who designed Monticello himself. I found his notebook replicas at least as fascinating as his stunning home.

Probably the most striking thing about Monticello is the sense of Jefferson’s genius that one gets from the place. Jefferson wasn’t simply a gifted writer who penned great documents; or merely the 3rd U.S. President; or a political elite who commissioned some great buildings; he was all of those things, and more. Jefferson was a philosopher, an inventor, a voracious reader in at least four languages and a self-taught architect who designed Monticello himself. I found his notebook replicas at least as fascinating as his stunning home.

A shortcoming of Monticello, though, is its superfluous treatment of Jefferson’s great contradiction: the genius that declared all men to be created equal owned over 600 slaves during his lifetime, of which he freed just two while still alive. Monticello itself wasn’t just a home, but a plantation. Signs indicate where slaves lived, and worked, but the complex juxtaposition of Jefferson as both professed opponent of slavery and prominent slave owner isn’t really explored or explained in a way befitting a great historic site, like this one.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks

[…] first secular university in the country, he designed UVA’s great rotunda (in addition designing Monticello, essentially creating the Library of Congress as we know it today, drafting the Declaration of […]

LikeLike

[…] secular university in the country, he designed UVA’s great rotunda (in addition to designing Monticello, essentially creating the Library of Congress as we know it today, drafting the Declaration of […]

LikeLike